Interview with Carole Osterweil conducted by Bartosz Zych

In the VUCA world project complexity continues to grow. We are introducing new tools and methods like AI so we can gather more information and improve project control. But will this focus on technology help us dealing with rising levels of stress and anxiety in the project management workforce? Are we missing something in our quest to lead and control complex projects? Carole Osterweil talks to Bartosz Zych about using ideas from neuroscience to regulate emotions, reduce project complexity and realise the benefits of tools like AI.

You’re interested in neuroscience as a servant of project management. Why this area?

Look at the evidence about project failure, it almost always comes down to the people stuff and the dynamics of human interaction. A study by Budzier and Maylor in 2021 put numbers on it. They discovered “Practitioners find turning around the people issues about six times more challenging than resolving technical problems. In other words, people, capability, and culture issues dwarf technical project issues by a factor of 6 to 1: people issues, 84.8%, technical project issues 15.2%.” [i] Yet the people stuff gets very little airtime in the education of most project managers. Look at history, and there’s a legitimate excuse – we didn’t have a robust model to explain why people behave as they do. But developments in neuroscience have changed that.

I’ve discovered that equipping project leaders with a bit of neuroscience enables them to cut through complexity and take better and more emotionally intelligent decisions. As a result, they deliver better project outcomes with higher productivity, in shorter timescales with less stress.

Fot. Carole's archive

Fot. Carole's archiveIn your latest book, Neuroscience for project success: why people behave as they do, you have gathered the newest knowledge on neuroscience and created a model that acts as a map for project managers in a VUCA world. Could you give us a short insight into this model and explain why it is an answer for today’s project management problems.

We are all familiar with the notion of a fight-or-flight response. We know that in the face of a big physical threat, like a car rushing towards us or a fire, we do whatever it takes to avoid the threat. Essentially, we don’t waste time and energy considering alternatives, we go on to autopilot to ensure we survive. When the threat recedes, the avoidance response recedes, and we recover the ability to weigh up alternatives. In the book I introduce Dan Siegel’s terminology to contrast the moments when our Thinking brain is offline (we are on autopilot) with the moments when our Thinking brain is online, and we can accurately assess risks and options.

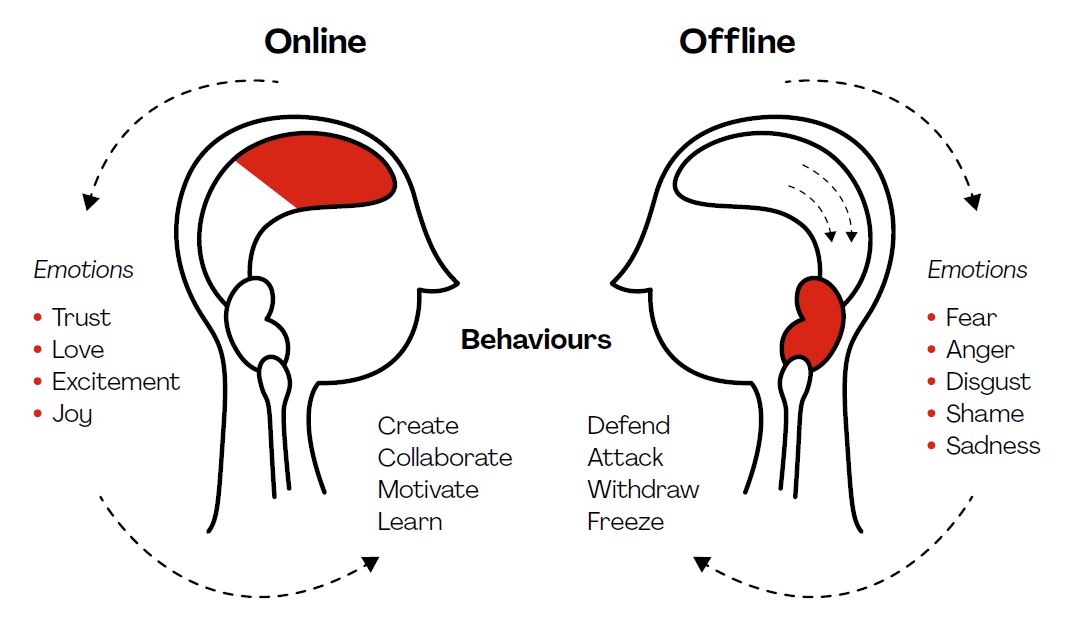

Neuroscience research tells us that the human nervous system does not distinguish between physical and social threat. Both can take our Thinking brain offline. And when it goes offline, our emotions and behaviour change [see Figure 1].

Figure 1. Emotions and behaviour change when the Thinking brain goes offline

Figure 1. Emotions and behaviour change when the Thinking brain goes offline

Copyright © Visible Dynamics 2018We need our Thinking brains online if we want to collaborate, be creative, motivate others or learn really well, (i.e. do all the things a project manager is meant to do). Now consider the projects you are working on. How often have you, a team member or stakeholder been a bit defensive or completely overwhelmed, felt angry, fearful, or ashamed, been aggressive, wanted to withdraw from the situation, or stormed out of a meeting?

There is no point in describing these emotions and behaviours as good or bad. They are all perfectly natural human responses to cues of threat. Whilst some are more extreme than others, they are all associated with our Thinking brains going offline. More extreme avoidance behaviour indicates a more intense avoidance response, and a Thinking brain that has been taken further offline.

Our responses to any situation are largely driven by our past experiences. And, because no two of us have had the same life experience, they are very personal. To give a simple example, we could sit in the same meeting and listen to a client ask about a milestone. I might experience the client as being aggressive, you might think them perfectly reasonable. It doesn’t matter who is right, humans treat imagined threats in the same way as actual threats.

The threat diverts energy away from our Thinking brain and primes us to take avoidance action. If the threat is big enough, our Thinking brain goes completely offline, and it takes a while to bring it back online. Project success depends on our Thinking brains being online. Understanding this changes everything! The model or map you refer to is straightforward. To succeed in a VUCA world, project managers need to be able to answer four questions:

- How online is my Thinking brain?

- How can I get it more online and keep it online?

- How online are their Thinking brains?

- And finally how can I get them more online and keep them online?

This grows our power skills, emotional intelligence, and ability to deal confidently with the people, capability, and culture issues – the challenges which are currently six times more challenging than technical factors to resolve.

Fot. Carole's archive

Fot. Carole's archiveNeuroscience sounds like “a lot to learn”. Is it learnable and applicable for project managers, who usually haven’t finished medical school?

Don’t be put off by big words like neuroscience! A leading professor of organization neuroscience, Paul Brown, once told me: “It’s a bit like a Christmas tree. Neuroscience research is continuing to generate lots of shiny new baubles – but what really matters is the Christmas tree itself.” Project managers don’t need the baubles, they need the Christmas tree – and that’s what I’ve put into the book. Focus on the Christmas tree. Use the ideas in the book to develop your ability to answer the four questions and you’ll see huge benefits!

You say that the traditional “command and control” management is not the best approach. Why? What does this mean for project managers who prioritize results and performance? What should they do to switch to another management style?

I explained earlier how social threat takes the Thinking brain offline. In the book I introduce the five sources of social threat using David Rock’s SCARF model. SCARF stands for: Status, the perception of being considered better or worse than others; Certainty, the predictability of future events; Autonomy, the level of control we feel able to exert over our lives; Relatedness, the sense of being connected to others and part of the In-group; and finally Fairness, the sense that we are being respected and treated fairly in comparison to others.

When people sense a change in any one of the SCARF factors, it can activate an avoidance response – the bigger the change the stronger the response. People who adopt a command and control style are usually blind to the neuroscience and SCARF. They frequently find it difficult to keep their own Thinking brains online. This results in emotions and behaviour which take other people’s Thinking brains offline.

Strong emotions get amplified in groups. A leader who relies heavily on command and control can activate avoidance responses all over the place – creating unnecessary stress and making it far harder to get, and sustain, the results they are seeking. When you understand how the brain works, you prioritise results and performance by keeping Thinking brains online. Relying heavily on command and control does the opposite!

You ask what a command and control leader should do to switch to another management style. I’m not in the business of telling anyone to switch style. I want to encourage everyone to read the book and to try out some of the tools and ideas in it. For example, use the SCARF model to consider ‘how might I introduce this change without creating lots of uncertainty and reducing the team’s sense of autonomy about how they work?’ The last section of the book is designed to help readers experiment and learn what works for them. The key is to approach these ideas with curiosity and ask, ‘what might I learn?’ Do this and I’m sure you won’t be disappointed.

How does stress relate to the brutal and toxic organization cultures you discuss in the book?

We’ve known since the early 1900s that there’s a relationship between the brain’s level of arousal and our ability to perform a task. When we have lots of time and little to do, we can find it hard to focus and performance suffers. The brain needs a degree of stimulation to operate at its best. But too much arousal makes us stressed, anxious, and even overwhelmed. We lose the ability to focus, we have less emotional control and the quality of decision making deteriorates. The trick is to find our sweet point, where we have just enough but not too much stress. Using Dan Siegel’s terminology, at the sweet point, our Thinking brain is fully online.

The challenge is our VUCA world (remember VUCA stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity). Its very nature means it’s stressful and difficult to keep our Thinking brains online. In the book I observe that many organizations and leaders fall into the trap of seeing stress as an individual issue. In my view, it’s crucial to recognize that stress can be systemic too.

Excess stress often leads to what I describe as the Project Stress Cycle, characterized by falling levels of trust, which impact the quality of collaboration, innovation, and decision making [See Figure 2]. Separate research concludes that in the context of complex projects, command and control often creates unnecessary stress, mental health problems and problems with a toxic culture.

Collin Smith of ICCPM explains how it happens and what is needed in a podcast: “Unfortunately, there’s a trend: leaders in these projects keep pushing and pushing to the detriment of their own mental health and that of their teams. And productivity suffers… They tend to crank up the stress to get things done. Yet our research tells us when complex projects get really tough the opposite is needed, we need leaders at their very best in terms of critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and adaptability. We need leaders who despite the overload and stress can slow down rather than becoming more transactional and process driven.”[ii]

If you want to create a culture of high performance, you must take the human fight or flight response into account and actively work to keep your own and other’s Thinking brains online. In other words, you must nurture the group phenomenon of psychological safety.

Figure 2. The Project Stress Cycle

Figure 2. The Project Stress Cycle

Copyright © Visible Dynamics 2018Do you believe that organizations with brutal and toxic cultures are going to be in the minority in the foreseeable future? Why?

I hope they will be in a minority sooner rather than later. There is a growing understanding of the impact of a brutal and toxic culture on long-term organizational performance. This, combined with the mainstreaming of the ideas I discuss in the book such as psychological safety and the growth mindset, is leading to a growing and compelling evidence base that organizations will find increasingly hard to ignore. Add the challenge of recruiting and retaining good staff. Then ask yourself ‘what kind of culture do I want to work in?’ So yes, I am hopeful.

What do you think of the drive to introduce tools like AI to increase project control? What is better: the data driven decision making associated with these tools, or decisions based on feelings?

We like to think our decisions are completely rational and informed by conscious situational assessments such as ‘Have I seen this before? What data do I need to make a judgment call?’ However, if there’s an element of uncertainty, these conscious assessments are only part of the story. There are two other inputs, both subconscious, that have a big impact. Both are driven by our innate human drive to survive. These are: our automatic reactions driven by subconscious mental shortcuts and cognitive biases, and our raw visceral emotions.

True data driven decision making needs to account for these inputs too. We need to recognize it’s not possible to take feelings out of decision making! The bottom line is we need our Thinking brains online to examine and counteract our biases; to understand what our emotional responses are telling us; and to use AI intelligently.

The ideas presented in the book are crucial if you want to create a healthier workplace and reduce project complexity. Without them, we will fail to capitalize on the potential of tools like AI, and people, capability, and culture issues will continue to dwarf technical project issues by a factor of 6 to 1.

Thank you for your time and great insights.

Thank you, and I hope we can discuss more during 18th International Congress PMI Poland Chapter in Warsaw.

[i] Budzier & Maylor quoted in Vyas,V, Zweifel,T (2022) Gorilla in The Cockpit: Breaking the Hidden Patterns of Project Failure and the System for Success, p3

[ii] ICCPM and Visible Dynamics, (2020) Stress, Culture and High-Performance Project Teams, Available at: https://soundcloud.com/user-680350226/stress_culture_high_performance_project_teams (Accessed 10 June 2021)

Known for bringing an understanding of how the human brain works to the worlds of project management and business transformation, Carole’s on a mission: to make the invisible people dynamics which get in the way of delivery visible – so we can do something about them. Her book Neuroscience for Project Success: why people behave as they do was published in 2022, to critical acclaim. She’s an accredited Executive Coach, whose work includes building the UK Government’s senior change and project management capability at Cranfield University.

Człowiek renesansu, którego motywuje możliwość rozwoju i nauki. W swojej pracy uwielbia łączyć zdolności analityczne z umiejętnościami miękkimi, dlatego swoje doświadczenie zawodowe zdobywał jako konsultant, koordynator projektów unijnych oraz key account manager. Obecnie jako kierownik zespołu realizuje w Centrum Innowacji i Biznesu Politechniki Wrocławskiej projekty łączące naukę z biznesem. Prywatnie mąż i ojciec. Po godzinach wędrowiec po okolicznych lasach. Wierzy, że różnorodność to zaleta, a nie wada i że mniej oznacza często lepiej.