The roots of practical management theories and trends can be traced back to the natural process of forming managerial structures. However, for a long time, these theories and trends remained unnamed. With the development of science in the 19th century, not only was what had been practiced for millennia given names but also directions were sought in which management science would evolve. Thus, management transitioned from a pre-scientific period, mainly focusing on organizing enterprises in a military form (also known as “red management”), to scientific justification and the interdisciplinary nature of management sciences.

What do we know so far?

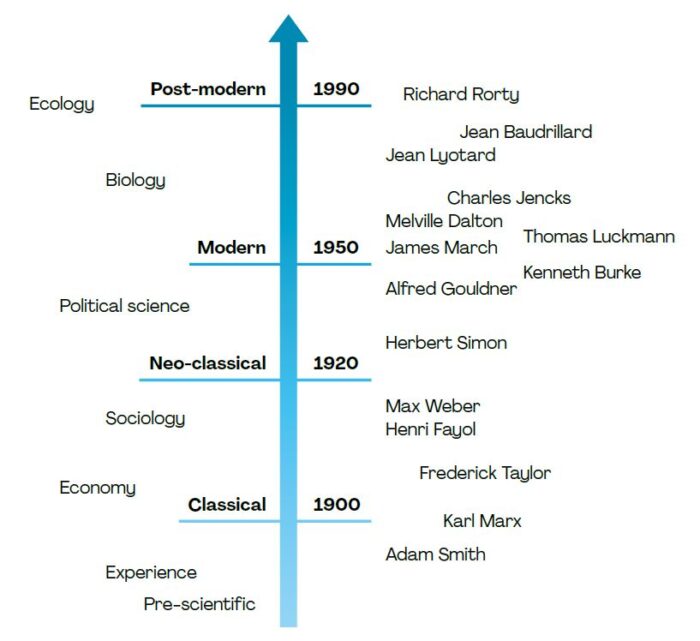

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, numerous representatives emerged who described the existing state, outlining classical trends. True pioneers in this field, such as Henri Fayol and Max Weber, can be mentioned. Nor can we forget the first scientific methods for profit maximization introduced by Frederick Taylor, whose methods were later labeled as the “technological trend” or “Taylorism”.

Progressing into the 1930s, Elton Mayo not only theorized but also conducted research in the Hawthorne plants, where he also focused on employee satisfaction, communication issues, and relationships between employees and managers. Subsequently, these trends delved more into interdisciplinarity.

In the 1950s and 1960s, with the development of organizational psychology and sociology, the behavioral trend emerged, focusing on studying human behavior and motivation in the context of organizations. Authors such as Douglas McGregor (Theory X and Theory Y) and Abraham Maslow (Hierarchy of Needs) contributed to the development of this theory. This period also brought about the integrative trend, which included systemic approaches, focusing on perceiving organizations as complex systems, as well as situational directions or the contingency trend, emphasizing that there is no one ideal management approach, and effectiveness depends on the context and external conditions.

Fig. 1. Evolution of management theory

Fig. 1. Evolution of management theory

Source: author’s own elaborationTeal organizations as a cure-all?

Considering the mentioned context and external conditions, we cannot ignore that not every organization can afford a teal work organization. It’s difficult to imagine a production-focused organization where employees decide on every aspect of production. This doesn’t mean that such workplaces cannot adapt to the times; concepts like Kaizen and Lean have existed since the 1950s, allowing for bottom-up work improvement and encouraging lower-level employees to suggest ideas to enhance efficiency.

Consequently, we can point out that teal practices are best suited for modern organizations engaged in project work. It also seems that teal should address the current needs of both employees and employers. It offers freedom of decision-making within teams, work organization, and the elimination of middle management, which often dampens enthusiasm through bureaucracy. However, if this is the case, why do we often hear about burnout, apathy, and the phenomenon of moving from one job to another, only to experience the same feelings shortly after?

Cyan, or stem cell teams

I believe that this phenomenon of moving from one job to another can be seen as a lack of success in modern methods and the subtle difference that distinguishes teal from cyan. Let’s start with the color – why cyan and not a complete departure from blue, for example, into indigo? As we know, teal organizations are characterized by flexibility and bottom-up organization, exemplified by agile teams. Teal, similar to stem cell teams, accomplishes tasks through team self-organization. However, teal organizations, unlike stem cell organizations, assume that each employee, upon entering a project, knows their role perfectly and is responsible for their well-defined zone. This is the main difference from teal. Given that there is no significant leap in the idea itself, we can’t introduce a new color, only a shade.

Stem cell teams can only form in organizations with highly specialized employees, a non-essential requirement for teal. Therefore, organizations centered around projects would benefit most from this solution. In such cases, employees understand the organization’s needs and aren’t afraid to take on tasks. When a new project arises, employees are knowledgeable about it and can assign themselves to the project and outline their responsibilities during the initial project meeting. This isn’t the case in teal, where employees decide on the project, but upon hiring, they already know their scope of duties, and any expansion or reduction of this scope is minimal.

In cyan, the project manager can take on roles such as analyst, product owner, or even a developer if they possess the necessary skills and want a break from their primary role. The same flexibility applies to all team members. This is an excellent response to the quick burnout experienced by younger workers today. Such solutions also encourage self-motivation among employees without relying on financial incentives. Additionally, employees lose motivation to switch organizations, each project offers new challenges and a chance to expand their experience. In this case, the organization becomes a network of stem cell teams – just as a cell within an organism can assume various roles during development, a member of such a team can take on any role within the team.

Will stem cell teams work?

This question always arises in all considerations. However, it’s important to remember that stem cell teams are currently a purely theoretical concept. Nevertheless, when Fayol described teal teams, he didn’t have any examples, and his concept was nothing more than that. Even in modern times, many companies that claim to embrace self-organization and teal principles don’t fully implement them.

Often, self-organization is limited or incorrectly identified as the flexibility to complete tasks within agile teams, which doesn’t correspond to the above concepts. It’s essential to trust employees’ hand projects to the highly specialized hands of an expert and relinquish middle management for the success of both teal and cyan. If we consider small startups as the closest examples of cyan, their diversity and rapid progress demonstrate that it’s possible to succeed in such apparent chaos, implying that stem cell teams can successfully carry out tasks.

A long-standing project and delivery manager. Developing in project management not only as a practitioner but also as a theorist, constantly deepening his knowledge through both academic and non-academic learning. A propagator and creator of the idea of stem cell teams.